Community Development and Savings October 1994

It was time to start our development work. The values underlying our development work required that we work with people in a way that would bring out their best without fear of reprisals. It required that people truly could make their own decisions, choose what they would like to save for. It required accountability for their decisions. It required trust.

Cambodia was just emerging from the horrific past 40 years of war, genocide, isolation. Everyone was deeply traumatized, deeply hurt. There was very little security yet for the nights were filled with shootings and grenades and no one felt safe. The staff were no exception. They were terrified to leave the safety of the office, terrified of people they would have to meet.

The litany of excuses began of why we could not do development, couldn’t do savings. The people were too poor, they did not have money. My response was show me a person with no money. The people are bad and they will steal from us, kill us, not trust us, they are lazy. My response, who told you that? Show me a lazy Cambodian!

The arguments continued for several weeks. I finally said, we, you and I, are the barriers to development because we don’t let the people speak instead we speak for them. We will never be able to help anyone with our prejudices! You have a choice, we will develop a baseline questionnaire asking people about their life’s realities and then we will decide our best approach to helping people.

Their resistance continued until I finally said, you have a choice, keep your job and go to the poorest and talk with them or you can quit right now. Vutha was the first to take up the challenge. She left the office to go to Kilometer 6, frightened and at the same time angrier than I had ever seen her. She returned several hours later, her face lit up with unbelievable joy. What happened, I asked.

Vutha told her story. She had driven her motorbike to Kilometer 6, determined but terrified. Kilometer 6 was one long road of unbelievable poverty at that time. She had stood at the top of the road and started to sob, so terrified she was. She couldn’t stop crying until a woman stopped and asked her what the problem was. Vutha poured out her heart to this woman. She told her how she had to interview poor people but she knew they would hurt her and laugh at her. The woman gently asked her to come with her.

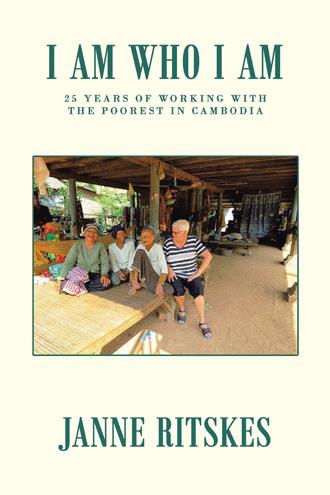

In the depths of the village, the woman invited her to sit down on a mat in front of a very small thatched hut. 7 children appeared from all directions, the woman’s husband appeared, dressed in a krama and nothing else. The children were severely malnourished, dirty and dressed in rags.

The woman apologized that they had no food to offer her but instead asked one of her children to get the last remaining coconut out of the house. She told Vutha to go ahead and ask her questions for she was poor. Very quickly, neighboring families joined in and family after family answered her questions. Vutha visited each small shack, she was welcomed wherever she went, she saw and felt the poverty around her. What changed Vutha that morning was that each family offered her whatever food was left in the home, a piece of fruit or a scrap of rice, she was welcomed wherever she went. She had returned to the office to pick up more surveys and couldn’t wait to return to the village. This was the start of our development work.

A few days later, Vutha and Soklieng and myself went to Kilometre 6 together. The poverty was so very stark and hurtful. I taught them what a target population was. In order to find the poorest of the poor, we had to set a baseline. This baseline turned out to be anyone who made an income of 0 to 1000 riels a day, roughly 15 cents a day. Both ladies had worked with poor people before or so they thought. Soklieng became very disturbed. They had found the poorest people and it was much different than what they had believed. Soklieng, who always said she was poor, said that she would never say that again. That made my day.

We found 8 very poor families in very short order. It turned out that 2 of the women were able to sew. We decided that both should come to the office and be trained to make our products. Tabitha would buy them both a sewing machine which they would repay out of their earnings. Chanthou had changed dramatically from being a suicidal cleaning lady and had become a transformed woman. She a teacher of others. She would teach these ladies how to sew the products. What a change that was! Unbelievable. It made all my efforts with her worthwhile.

2 other families made Cambodian designs out of beaten tin. Again, they are very poor and had little market for their product. The girls said we had to find a market for their work. One of the things we did was to sew a few of them on the stockings making them really Cambodian. Another fellow was severely handicapped because of stepping on a land mine. He made money for his family by begging. There was no end to the poverty. Everyone looked much older than they were, they looked so very tired and beaten. We decided to start community development in earnest. We chose Kilometre 6 as our first village where 3000 families lived in absolute poverty.