I visited my birthplace, the Island

of Montserrat, in the summer of

’94. It was hotter than usual. No one could explain the surging

temperature. Swarms of earthquakes shook

the Island almost daily, and while I was alarmed, the

residents shrugged them off as mere annoyances.

The house vibrated.

“Did you feel that?” my cousin

asked.

“Yes. What was it?”

“Another earthquake,” she said

casually.

I wondered if they knew the

consequences of such tremors. I no

longer had any doubt, when she showed me the diagonal split on the wall of the

master bedroom.

“We’ll fix it soon,” she said.

Later, it was my turn to show her

the crack on the wall of the formal dining room. I helped her to remove the fallen

plaster. I thought that my relatives

were either fearless or stupid to be so callous about living on an Island

where earthquakes were so prevalent.

Then I thought of the people of California

who also live under the threat of destruction by earthquakes.

The following day, we visited our

family’s homestead. My great-great

grandfather had built the house at the close of the nineteenth century. The more affluent relatives purchased

property in the prestigious neighborhoods of the Island

and only visited the family’s land to harvest its fruits and vegetables in

season. I looked at the old house, and

thought, “I was born here.” I imagined

hearing the voices of my brothers and sisters as we ran from room to room,

playing hide and seek. I begged my

cousin to open the house. We

entered. I opened its windows and doors widely,

and examined each room. The floors

squeaked. Daylight filled the rooms once

more. Though cobwebs hung from the

rafters, I told myself that I would retire there some day.

I stood at the portal, and

observed the fruit trees. They hung low

under the weight of their fruits. It was

then that my cousin revealed something I had not known before.

She said, “I remember the night

you were born. Grangran,

(the name given to our great-grandmother) buried your umbilical cord at the

root of that tree.”

She pointed to the oldest coconut

palm on the property. I felt my whole

body tremble. I ran to the tree and

attempted to embrace its trunk. I hugged

it as I would have hugged my deceased mother.

I felt a strange bond with it. My

heart beat rapidly.

I broke away and admired the

palm. It stood tall. Its green fruits clung together in

clusters. I remembered drinking water

from its fruits and eating the delicious jelly from its husk in my

childhood. No one bothered to pick its

coconuts any more. Dried branches and

fruits lay at its base. My relatives had

long planted dwarfed coconut palms whose fruits were accessible from the

ground.

“I would like to drink water from

its fruits again. Can I get a boy to

pick some coconuts for me?”

“Not in Montserrat,”

she said. “Boys don’t climb tall coconut

palms anymore. That’s why we planted the

grafted ones. You can have as many

coconuts as you want. You’re tall

enough. Just reach up and pick them.”

“No thank you,” I said.

I selected six of the dried coconuts

from the base of my special palm and took them to my cousin’s house. I took a machete and ripped off the dry

husks. I opened three coconuts, threw my

head back, and drank the sweet, mellow water.

My cousin mimicked me and laughed heartily.

That evening, I made coconut pies

for the family. While they ate, I

reminded them that the coconuts were from the palm tree that was nurtured by my

umbilical cord. I returned to the homestead

and embraced my special palm several times that year before I returned to New

York.

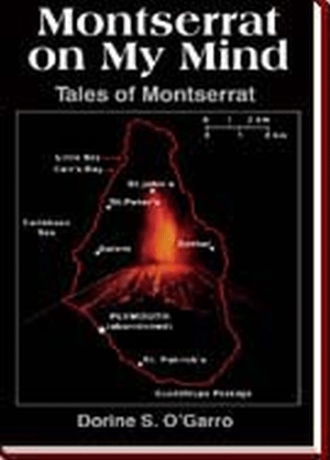

In the summer of ’95, scientists

revealed the reason for the swarms of earthquakes. The volcano at the Soufriere

Hills erupted on July 18th.

The first eruptions claimed my family’s property, burying it deeply in

tons of pyroclastic flow. It was sad enough to lose the old house and

the thirty-two acres of land, but I cried for the old coconut palm, for like

all of my ancestors, it too was lost forever.