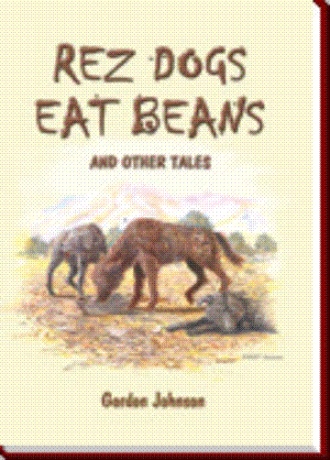

Rez Dogs Eat Beans

Once my cousin Goose, who used to sport rich women in Palm Springs, brought an Afghan hound home to the Pala Indian Reservation.

My guess is that the dog was owned by some tanned, tennis-playing woman who decided to spend the summer sunning her wares on the French Riviera, and Goose couldn't abide just letting the dog mope in a kennel.

So he took pity on the thing. Pampered all his life, O.D. came high stepping onto the reservation, silky hair brushed to a sheen, toenails clipped, teeth pearly white. A city dog.

O.D. was none too bright, either. Tell him to fetch, and he'd sit there looking goofy, as if saying, "Which way did they go, George? Which way did they, go?"

He ran like a 13-year-old boy who grew too fast. I can picture him now, all loose and gangly, padding down the dirt road toward Goose's house, singing, "I'm bringing home a baby bumble bee, won't my momma be so proud of me."

People used to make fun of O.D., myself included. It was plain he wasn't cut out for reservation hardships.

A couple of months later, you wouldn't have recognized poor O.D. Mud and twigs clung to his matted coat. He took to sleeping on the roof of Goose's car at night to make it harder for the other dogs to get at him. He seemed to have developed a nervous tic.

Needless to say, O.D. didn't last long on the rez. I'd like to think he's still loping across the desert, hellbound for his Palm Springs groomer. But more likely, he was hit by a gravel truck, or killed in a dogfight, or shot dead for chasing cattle.

Anyway, one day, he just disappeared.

Such is the fate of many reservation dogs, especially those not born to the life.

Nearly every reservation household has at least one dog. Many have two or three. With no fences, the dogs have the run of the place, free to do as they please.

In the morning, some chase rabbits through the willows and cottonwoods across the river. As the day heats up, they'll nap in the shade of the Mission San Antonio porch, or under the pepper tree behind the Pala Store.

Some dogs follow their kids to the mission school, where nuns throw blackboard erasers at them to chase them out of classrooms.

Others stick close to the back porch, ever watchful for a half-eaten tortilla roll tossed their way or a greasy frying pan that needs licking.

I get a kick out of dog food commercials, like the one where the guy's champion Weimaraners point quail and dive headlong into the pond to retrieve downed ducks.

With nutrients scientifically balanced, his dogs only eat the best, he boasts.

Reservation dogs eat beans. A dog that won't eat beans doesn't survive.

A woman who gossips too long at her friend's house and returns home to find her pot of beans scorched, doesn't throw them out. She dumps them into the dog dish.

"That ought to hold you for a few days," she says. Eat or starve. That's the rule.

Reservation dogs are tough. They're known for it.

People will say when trying to saw through a fried round steak: "This meat's tougher than a reservation dog."

Or: "That Rosie sure is cranky, she's meaner than a reservation dog."

Or: "Joe's chasing that skirt like he's a reservation dog."

Dogs born on the rez have the playful puppy days to form alliances. They find a place in the pecking order, and hold to it, or suffer a whipping.

A top dog will usually have one or two sidekicks he's groomed over the years to back his play.

There was once a burly dog, mottled black and blue, named Shindig, who ruled the reservation for what must have been a decade. Shindig was pure mutt, but like I said, a brute. His backup was a dog named Duke, a German shepherd skinny as a razor blade with teeth just as sharp.

They liked nothing better than to rain misery on unsuspecting newcomers.

Shindig would launch the frontal attack, while Duke went around back for the huevos. More than one reservation dog went around with a half-empty sack.

So it went. And so it goes. A dog's life on the rez.