Aged 74, this is Richard Smythe’s first published book but he is no stranger to writing. Fifty years ago he decided to become an English teacher and, whilst training, he edited the college magazine and was passionate about drama, producing plays, acting leading roles, writing material of his own and organising a production at the Edinburgh Festival. When he entered the classroom he sought to develop, above all, his students’ creative expression, writing short stories of his own as an incentive. He met opposition from some quarters and eventually switched to his other strength, music, taking a piano diploma and becoming Head of Music in a Shropshire school where he developed a successful band and small choir which won several festival awards. Here again he wrote much original material.

Retiring from class teaching he became a visiting instrumental teacher, allowing him time to write short novels, one of these for children with songs included at the end of this book. The bulk of the poems selected here, however, were composed during walks in the Shropshire countryside with the addition of a few earlier works.

His main theme, from the beginning, is the relation of human events and feelings to the natural world, in all its beauty and continuity. Even back in the 60’s in Drone’s Lament he associates all the excitement surrounding the return of the first American astronauts back from space with the extraordinary mating flight of a queen bee. A lonely drone, unsuccessful in this once in a lifetime, suicidal quest, hovers over the scene, pondering his future.

This feeling of loneliness appears in another early work, Meet me at the Festival Hall, when he is waiting on the paving slabs of South Bank in the company of an Irishman,

‘Standing chessman singing ballads’ whilst people fell from the walkways ‘like bagatelle balls’ with ‘high heeled determination to appear their best at the Sunday afternoon concert’. In Granville Park also features a chill feeling of desertion ‘In the greyness/ Of a mining country’ where ‘the galled earth/ Agonised with its burden of mud and stone’ where he was ‘Waiting while tiny specks of snow/ Fell as white soot from a darkening sky’

Not all is gloom in these personal reflections, however. It was a Sunday recalls a first meeting on the morning after a blizzard when ‘The mother of all earth’s fire / Gazed from a gentle height and with gentle warmth/ Into the fondness of your face’ and ‘A tablecloth of the purest white’ upon which a spreading tree was ‘Holding candles to each corner.

Another poem that sparks feeling of glowing love is Your smile: ‘Your lovely smile / Stirs my senses as if / Waking to the first rays of an alpine sun / On the ridge of my tent / I feel a growing warmth that last all day’

Anguished pity is another emotion which surfaces in The daffodils where Richard Smythe likens the wrenching of one’s love to a flower which has no ‘shining steel’ in its defence and carries a ‘burden of cruelty’ that is ‘whispered to the earth’.

And in Was it you? there is regret that too late a motorist with ‘morning cares’ and ‘windscreen wipered’ eyes does not stop for a loved one.

Not all poems, though, contain gentle, soft reflection. In Heart of Oak there is a savage indictment of rich men’s plunder over the centuries: ‘The wrinkles on a peasant’s face tell a story / They do not betray his thoughts’ with later the question, ‘Silvered inheritor / Incline your head/ Whisper your prayer / Will you spill in the collection plate/ The same that was taken from the poor?/ Your aged, dry hands glide smoothly over my face……

Having fun with words and sounds, is a favourite subject, purely for its own pleasure and being memorable, as in examples of Mr. Smythe’s teaching methods. The limerick, The Pianists of Uppingham, teaches use of the piano’s sustaining pedal, an Instructional Ode tells children how to open out a folding music stand with asides like ‘Of course, this obvious, I hear you declare / My apologies to you all, and to Rupert Bear.’ There is a paragraph on class group work, using vowel sounds, with an account of a pigeon falling victim to a buzzard in Woeful Awe, and the longest poem of all, Turn of the Worm, not in verse, is a melodramatic diatribe, with performance notes, uttered by the essential but unappreciated common earthworm.

Truly this is a collection of varied ideas and verse for people of all ages and tastes. Richard Smythe recalls his own childhood memory in Chopin at Night of the dark years of the 1940’s when he was in bed listening to his mother playing the piano and now ageing himself is neither shy of publishing strong feelings about death in Tender Wish: ‘Carve no stone to remember me by / Lest it bruise you’ nor in laying down principles, about how we should care for each other and ensure the world’s continuity, in Conjure Not: ‘I would have embraced the world / But my arms, stretched like these brave oaks, / Are broken. They live to cast more seed / Whilst my life is spent

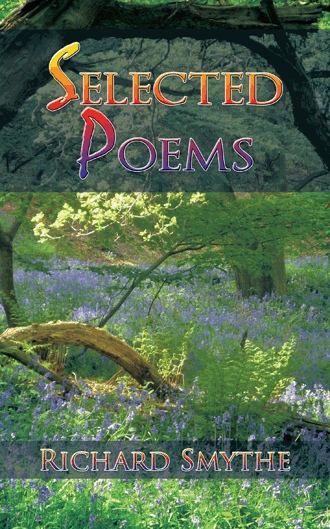

There is celebration in several poems in this collection and perhaps the most joyous is illustrated on the cover: Bluebells: ‘Morning assembled a woodland beckons me / Miraged in blue, as if the surface / Of a mountain lake was tilted against the feet of sturdy oaks’ ending ‘Come, my love / Be baptised in these waters of the woods / And wedded upon Nature’s highway.’

This slim volume of 29 poems and verse is easily slipped into the pocket and, hopefully, should provide pleasure at odd moments during a busy day.

Richard Smythe is able to recite his work, without script, at local poetry readings. For more information contact richardsmythe@blueyonder.co.uk