Pigeon Toes

Oh that I had wings like a dove!

For then I would fly away, and be at rest.

—Psalm 55:6

Jed had survived his brush with death, but the burn accident had left our son terribly scarred. Could he survive his upcoming teen years without becoming bitter? How many times would I yet ask myself, “What good thing can possibly come from such a tragedy?” The day Jed introduced me to a certain pigeon, my doubts took wing.

“Hey, Mom!” Jed called to me, “That bird needs help! Think I can catch him?”

My ten-year-old son stopped tossing bread crumbs to the flock of pigeons that surrounded him when he discovered one that appeared to be crippled. Jed loved all animals, but birds had always received his special attention, especially a bird in need. Before he was six years old, he had successfully raised a very young cedar waxwing and rescued a mockingbird fledgling from certain death on the highway. Then, at the tender age of eight, Jed was trapped in an inferno that left him with severe burns over nearly half of his body, and he was suddenly the one in need.

By a unique series of miracles, Jed’s life was spared. Through three long years of surgeries, countless checkups in US and Canadian burn clinics, he had maintained a cheerful spirit. For his sake, I tried to hide my tears, but I was on an emotional roller coaster.

I repeatedly asked myself, “Why did this awful thing happen to my little boy?” Then, as I witnessed more severely damaged burn survivors in hospitals and burn clinics, I secretly declared, “I am so thankful that this is all that happened to Jed.” I tried desperately to be brave, but somewhere between the strain of flashbacks and medical appointments, my smile would begin to wobble. Whenever Jed saw this happen, he would gently touch my arm and encourage me.

“Don’t cry, Mom,” his blue eyes would sparkle as he looked up at me. “Everything works!”

Every six weeks, leaving Jed’s father and his beloved dog behind, we traveled from our home in British Columbia’s Peace Country down to Vancouver for surgeries and check-ups. Jed’s progress was monitored with an ongoing series of photos taken by his plastic surgeon. He endured grueling orthodontic adjustments. He was assigned numerous therapies and splints designed to prevent muscular atrophy. He was fitted with customized pressure garments for his legs and hands to prevent his scars from thickening. We were thankful for sponsors to help us with travel expenses, but getting to appointments on time, finding parking spaces, and weighing the advice of various health professionals, was exhausting.

Jed was a country boy. The confinement of the city was harder for him to endure than his medical assignments, but he did his best to remain positive. I introduced as many simple pleasures as possible during our trips to the lower mainland. We played the story tapes parents that my parents recorded for Jed: Where the Red Fern Grows, Summer of the Monkeys, Midnight and Jeremiah, Summer Lightning, and Sarah, Plain and Tall.

This particular time, we had enjoyed listening to their newest series, I Can Jump Puddles, a book by Alan Marshall, an Australian lad who lost the use of his legs at age six because of polio. At the end of the story, Alan is moving to Melbourne to take an accounting course, far from his country home and his best friend, Joe.

“I wonder how you’ll get on with your crutches down there,” Joe mused.

“Crutches!” Alan exclaimed, dismissing the inference with contempt. “Crutches are nothing!”

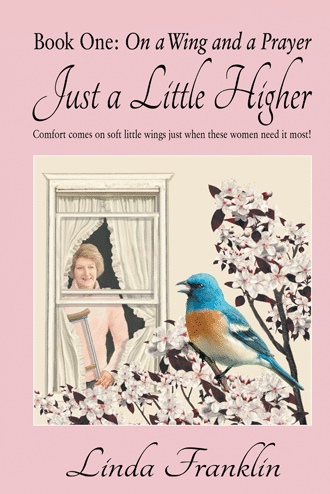

Alan’s wild adventures and disdain of sympathy impressed Jed. It seemed to me that he held his head just a little higher that evening as we carried our luggage into Easter Seal House, our home away from home.

The next day’s schedule was even more exhausting than usual, but Jed’s compensation for endurance was not an expensive gift or an exotic meal. All he wanted was some day-old bread and a visit to Granville Island; a paradise of fresh produce, book stores, coffee shops, restaurants, dessert bars, delicatessens, bakeries, art stores, and toyshops. With the relief of having our appointments behind us, we ordered a pair of fresh croissant sandwiches at the Island deli, plump with garden ripe tomatoes and crisp alfalfa sprouts, and then found a bench overlooking English Bay where we could watch the boats as we ate a late lunch. Jed finished quickly so that he could get to the main attraction; feeding the pigeons.

He discovered the crippled bird and walked back to me before he finished distributing his loaf. “See that one over there?” Jed pointed toward the rear the flock. “He’s limping. There’s some string and tar stuck on his feet. That bird needs help! Think I could catch him?”

“I don’t know, Jed,” I answered doubtfully. “He can probably still fly.”

He left his bread with me and tried to catch the injured bird, but the pigeon managed to stay just out of reach. Though he returned in less than a minute, Jed did not appear defeated.

“Let’s go to the Toy Factory,” he urged as I finished eating. “I think I can find what I need over there.” Bypassing tempting displays of kites, trains, games, and scientific models, Jed walked directly to a display case filled with butterfly nets. He paid for his purchase with birthday money that he had saved. Then, with scarcely a limp, he hurried back to the flock. Onlookers exchanged frowns while Jed eagerly sought his prize. Who is this masked child darting in and out among our pigeons?

Ignoring the stares to which he was almost accustomed after nearly two years of wearing his pressure mask, Jed captured his prize. Fish line was not only wrapped around the pigeon’s legs and toes, it was embedded in the flesh. The bird’s feet were red, swollen, and smeared with fresh tar. Wiping the tarry feet with my napkin, I saw that one toe was missing, and two others dangled uselessly, far past saving but too firmly attached for me to remove easily. The mess would require some sort of surgical procedure. I sighed, more worried about how I would remove the tar that Jed had just smeared on the new pressure gloves he had received that day than in how I could help his new friend.