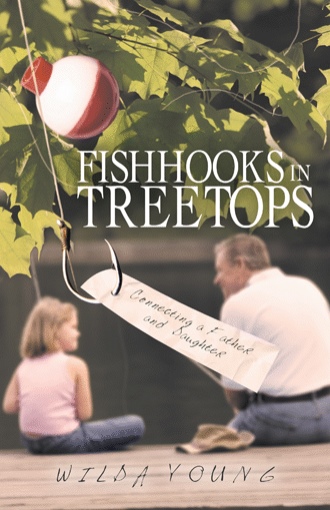

Fishhooks don’t belong in treetops. Lines get tangled and knotted, and the fisherman goes home empty-handed. Unless, of course, someone expertly untangles lines, sets things right, and helps the fisherman cast the lines properly.

My dad and I actually enjoyed fishing together. He did more for me than help me get my fishhooks out of treetops though. He taught me values, discipline, appreciation for life and learning, and so much more. He helped me to recall the simpler times of my youth and the incidents that shaped my personality. He reminded me that my relationship with the Heavenly Father is even more important than my relationship with my earthly father.

I wish that all fathers had his wisdom. I wish that all daughters could connect with their fathers, learning from them and depending upon them to help them mature into happy young women. I wish that all fathers and daughters could share wonderful memories.

That’s why I am sharing my Christmas present. . . .

Daddy had been inspired to give his seven children a gift, a book of letters. . . . I opened my letter and removed the single sheet of paper.

Nov. 30, 1995

Dear Wood,

I’m writing all you kids and telling them some of the things I remember. I’m going to put them all together and send each one of you a copy when I get them. I want you to mail mine back and a copy of some of the things you remember.

I remember one time you got a reaction to a bee sting. Boy, were we worried!

I remember how Ramona gave you her lessons when she started to school.

I remember one time we were at Chapel at a wedding. You weren’t very big. You said, “Daddy, let’s me and you get married.”

I remember one time on the 4th of July you and Ramona and your mother and I were down at Cairo for supper. It came a flood. You said, “I told you it was going to come a shower.”

I remember how you liked the organ at New Burnside and said, “It’s amazing how much you can learn in so short a time.” Dad

. . .That very afternoon I curled up on the sofa to begin my response. I had learned long ago that a promise made to Daddy had to be kept. The Kleenex box beside me, I let memory after memory flow to the page, adhering to no organizational method. The students in my composition classes would have given me a D. But Daddy didn’t care about grammar or structure. He wanted memories, and he wanted them immediately.

Dec. 10, 1995

Dear Daddy,

One of the things I remember is that you always refused to let us say, “I can’t.” We either figured out a solution to our problem, or we stopped complaining out loud, because those words were forbidden.

I remember that you bought the chihuahua Tinker for Ramona and me when I won the spelling contest in sixth grade.

I remember your singing of “It’s Real.” You certainly were hard to accompany, but I can still hear you singing that song.

You always insisted that we get an education. You said, “Get your education. Nobody can take it away from you.”

You spanked me once for going to bed the wrong way. You told me to take one route, and I chose to go another—under the quilt Mother had in frames.

Once Mother was reluctant to let Ramona and me ride the bus to a ballgame. Sadly we watched the bus pass our house in Cypress. Two minutes later you came home. You decided quickly that there was no reason we couldn’t go, so you chased the bus to West Vienna where we boarded the bus and went on to the game.

You paid me to type about a dozen bulletins for Tunnel Hill Church twice a month.

You took me fishing the day before I began my senior year in high school. I caught lots of catfish and a few trees.

I remember meeting you in the back yard at New Burnside on November 3, 1971. You put your arms around Ramona and me and said, “Girls, we’ve lost your mother.”

On September 28, 1981, you beamed when you saw Elena. You said, “This is the only grandbaby I’ve ever seen on the day of its birth.”

I remember that you preached a seven-minute sermon one Sunday night because you knew all of us teenagers wanted to go to Harrisburg. I don’t remember why we wanted to go, but I think the sermon was “The Rooster Crowed.”

I remember what Harlan Basham said about you at a revival at West Eden. He said, “Marion Mosley gives and gives until it hurts. And then he gives some more.”

Thanks for giving me these memories. I love you. Wilda Ruth

. . .One year when I reread the letters, I realized that the book had a flaw. While Daddy’s letter to me and my letter to him captured a major part of my growing up, I always had to fill in the details of each incident when anyone outside the family or even younger family members read the letters. “Just the facts, ma’am” was not enough. If I organized our memories and elaborated on them, giving details that Daddy had had no time for earlier, I could clarify what it was like growing up in the simpler times of the fifties and sixties, how it felt to be a part of a minister’s family in a small community of Christian believers. Perhaps more importantly, people would see what a blessing our Heavenly Father bestowed on me when he gave me my earthly father, Daddy.