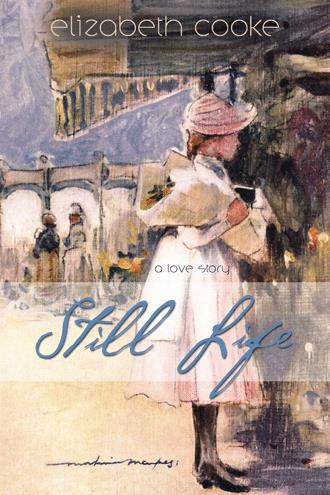

AN IMAGINATIVE STORY BASED ON THE LOVE BETWEEN PICASSO AND HIS YOUNG MUSE

1927 January Paris

GALERIES LAFAYETTE

1.

It is hard to define the line where dreams begin, especially in the mists of Paris, on a Sunday in January 1927. I am 17, a girl with a gentle face, made softer by those Paris mists, where frost in the air obscures all edges.

My hair is straight and blonde, cut in Dutch boy fashion, and I am wearing a Breton hat with red ribbons down the back. I have on my favorite dark green, wool Sunday suit, with black stockings and high-laced boots, looking the proper schoolgirl to passers-by, as I gaze longingly into the windows of Galeries Lafayette.

Galeries Lafayette is not an art emporium. It is Paris’ only department store where one can buy a pot or a sweater, even soap. It is a rarity in Paris to have everything in one shop. How much more sensible than to have to buy each item in a separate store, less tiring.

I gaze at a particularly intriguing new coffee machine in the front of the window. It is polished and gleaming and different from the usual filtre used to make coffee at home. Probably from America.

My name is Camille de St. Phalle, and I am the only child of an insurance broker. I go to the Lycée d’Athènes for young women on the corner of rue Monsieur, an elegantly risqué name for a street, about which my co-students love to giggle. I hopefully will finish with the Lycée early in the summer, providing I survive a set of examinations, the thought of which already chills me.

Rue Monsieur is on the left bank of the Seine, behind Les Invalides, Napoléon’s massive tomb and tourist attraction, and only a block from the Musée Rodin which is housed in the beautiful Hôtel Biron, adjoining rue de Varenne. The next street is rue Monsieur and my school.

To me, the Musée Rodin, in that wonderful old building, has a wickedness that delights. Perhaps the great sculptor’s reputation as “the scared goat,” and his obsession with women, old and young, makes me feel this way. It is said he had naked models all over the studio, and he liked to lie in wait, sketch book at the ready to catch them in some spontaneous pose that, in turn, kicked off an idea for a composition lying asleep in his mind.

I am not much educated in art, but I am aware in Rodin’s day (the 1880s and ‘90s particularly – although he did not die until toward the end of the Great War), it was the custom for artists to pose their models carefully, in contrived positions. With Rodin, he watched them freely – did not pose them at all. They combed their hair or read or rubbed one another’s backs. Then he would pounce with his pencil, drawing studies to be translated into clay and marble and bronze. They say he often pounced with something other than his pencil!