The most shameless displays of naked rock occur on the haunches of mountains. In outright defiance of gravity, these stony rumps are squeezed tightly and lifted skyward by colliding continents, raising crustal ‘tsunamis’ with crest lines that crisscross Earth. Fearing these stone waves, we baptize them with names – the Himalayas, the Alps, the Andes, the Rockies. These upsweeps of bruised stone are wild places that excite the two-dimensional drabness of our maps and the flatness of our imagination.

Appearances, however, deceive. Despite their rock-hard shoulders, mountains are ephemeral when viewed against the slow creep of deep time. Under the incessant blur of wind, rain, and ice, rock slabs crumble bit by bit until high peaks are denuded of their elevation. This recognition propels the mind’s eye to see beyond itself, which may be the reason why so many people are drawn to the wildness of mountains.

But why risk life and limb climbing mountains, you might wonder? It’s because they are mysterious, bewildering, and perilous. Although their vertical exaggerations provoke foreboding and horror, large mountains are dangerous more so for their weather than for their height. Sky-scraping mountains are about the deep secrets of winter, the punishing logic of cold, avalanches, and glaciers. The serrated rock ridges that step up to the peaks of tall mountains are chiseled into statuary by icy whorls of violent air, the freeze-and-thaw cycles of night and day, the avalanching of heavy snow pack, and the downward glide of glacial ice, all of these mere afterthoughts of severe and unremitting alpine weather.

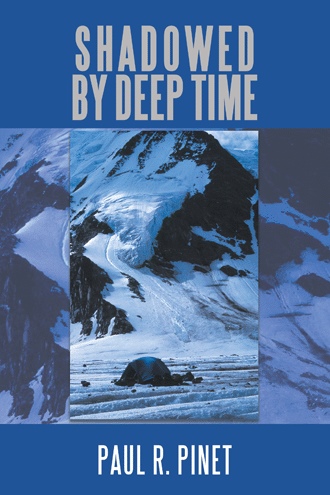

Long ago in the out-of-the-way Dry Valleys of Antarctica something special happened to me. It was mid December, the apogee of summer when temperatures hover between cold and very cold. There is no night at that time of year. Two of us were camped high in a misfit boulder valley that had melted out from under the ice cap, now several kilometers away. We were geologists at the bottom of the world, a peculiar place where south is squeezed down to a point and north is everywhere else.

As we feared, the narrow valley where we were encamped turned out to be a luckless place. There, we endured a windstorm for two days, pinned down shoulder to shoulder in down sleeping bags, hardly moving as if mummified in death. Torrents of heavy air coursed off the ice sheet and slammed against the canvas walls of our tent. The cold and desperate conditions alternately sharpened and dulled my uneasy mind.

Somehow, each blast of wind was rebuffed, thousands of them. How? I cannot say other than we did nothing special to deserve that outcome. What was it like? W. H. Hudson described a madhouse of a windstorm in Idle Days in Patagonia. “And the winds are hissing, whimpering, whistling, muttering and murmuring, whining, wailing, howling, shrieking – all the inarticulate sounds uttered by man and beast in states of intense excitement, grief, terror, rage, and what not.”

After the maelstrom, I wanted fresh air, lots of it, and space to breathe it in. My feelings needed sorting out. We both had to cry, but not together. I shouldered my rucksack and left, trudging upslope on lonely wind-packed snow. My destination some two kilometers away was a minor ridge in sharp shadow. I needed quiet time watching the polar icecap.

The true and easy feel of my body’s weight in motion exhilarated me. In no time at all, I reached a scree band at the foot of a sandstone ridge. The air was dreadfully cold and dry. Once safely on the ridge crest, I looked south to the pole. No human had ever been here before. In front of me, an endless apron of frozen water, wider than ocean-wide was drowned in muted light. Honey-colored clouds front lit by the low sun were weakening. I stared into vastness, not memorizing, but clumsily folding the gripping view into my head. Not a breath of air anywhere, the measured hush absolutely still, containing nothing whatsoever to overhear.

Unnerved by the deadness of the moment, I turned away. Everything, absolutely everything, was locked away in the graveyard of deep time. No smudges of lichen or moss, no blades of grass, only the carbonized impressions of Permian ferns splayed out on the bedding planes of thin shales. Nothing anywhere about was alive but me. Absolutely nothing. Somehow, I had not approached, but had passed through a portal where everything caused ache.

Not much later, the clouds drained the radiant light out of the polar ice and slowly fused the sky and ice into an immense expanse, a seamless wholeness, a world devoid of parts. The familiar sweep of space disappeared. My eyes forgot my mind. No horizon, no up or down, no inside or outside, no color, no sound, no smell, no time, no life, no memory, simply wide-openness filled with silence. The infinite underbelly of the cosmos had engulfed me, my solid body waned to no thing at all. Somehow, I was free falling into a vastness, the infinite, an unearthly void, a faceless enormity well beyond the clutch of words and rationality. I had unintentionally come upon my authentic self. I cried.

Gifts of darkness, solitude, and pain underscored by senseless mountains of ice and stone scraped me raw on that notable day of my life. I stood stripped of memory, dreams, and intellect. I encountered the unblemished clarity of raging nonexistence. Over a lifetime, that special involvement with the pervasive nothingness of mountains has hovered inside of me everywhere I have climbed. The all-embracing intimacy of impermanence is the vital essence of all that was, is, and ever will be. Yes, great, upright rocks in mountains fall apart without regret. The deep simplicity and completeness of that unvarying poetry, whereby everything matters and so nothing matters, infused my being. From mountains, I learned that I am simultaneously so much more, and so much less, than the human I appear to be.