But even worse than these was a large picture he brought for my purchase the first week in December 2009. Debbie was with me in the living room as he smiled and placed the picture upright on a table for my viewing. It was again large, 30X40 inches, with a haphazard conglomeration of white, grey and black acrylic paints splashed on canvas. There was no rhyme or reason what the artist was painting in this repulsive work.

I took a breath, ready to give my well-rehearsed plaudits when Debbie put her hands on her hips and leaned toward her husband. She said with a stern voice, “That’s perfectly terrible. You’re Barclay Sheaks, one of the world’s great artists. That’s not the work of a master artist. It’s piece of crap.”

I was shocked by her words. I attempted to add words of praise of his work when tears flowed heavily from his eyes. He tried to speak, but his lips only quivered in the strongest Parkinson’s tremors I’d ever seen him display. He lifted his picture and in a staggering gait, rushed from the room. I started to follow but Debbie held my arm. All the reassurances and praise I’d given him for the many other “bad” paintings were left unsaid.

“He’ll be alright,” she said again. I thought she would follow and comfort him but instead she went upstairs to the bedroom there.

I was aghast at that scene. Debbie’s words disturbed me, words that to this day she denies she ever said. But I was there as she uttered those derogatory remarks. My Vanderbilt teachings rang in my ears as I thought of the damage her words might have on my friend. I regret that I did not have a camera to photograph that picture.

I couldn’t sleep for several nights. I called often but Barclay never lifted the phone. When Debbie answered, she said that he’d “get over it and call me soon”. Christmas passed without my usual visit to the artist and our holiday drink. He always gave me a painting. My usual gift to him was a bottle of whiskey, a bottle of good quality wine, or some article of hunting equipment or apparel.

I went to his home several times and knocked, but he was never available. Then in the first week in January, I received a call from him with the brief message: “I have a picture for you.”

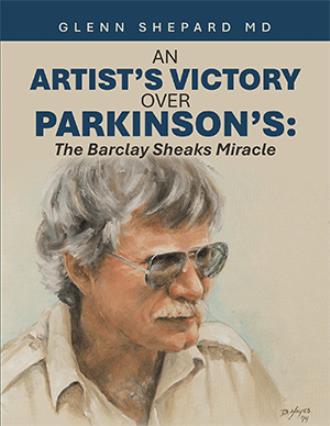

I hastened there and Debbie ushered me to his studio. He looked at me in a quizzical manner such as he’d never before displayed. He pointed to his easel. There I saw the shock of my life. On the same canvass on which he’d painted that perfectly awful picture a month earlier was a real Barclay Sheaks work, in the style of his many masterpieces of the past. I could have cried, tears of joy at that moment. I was speechless but he knew I was pleased. Barclay and I were never “huggers”, but that day I gave him a big one.

But even worse than these was a large picture he brought for my purchase the first week in December 2009. Debbie was with me in the living room as he smiled and placed the picture up on a table for my viewing. It was again large, 30X40 inches, with a haphazard conglomeration of white, grey and black acrylic paints splashed on canvas. There was again, nothing recognizable as a re-creation of any earlier painting, not even with the best of my imagination. There was no rhyme or reason what the artist was painting, and unlike Figure 30 that at least gave good vibes, this incited depression.

I took a breath, ready to give my well-rehearsed plaudits when Debbie put her hands on her hips and leaned toward her husband. She said with a stern voice, “That’s perfectly terrible. You’re Barclay Sheaks, one of the world’s great artists. That’s not the work of a master artist. It’s piece of crap.”

I was shocked by her words. I attempted to add words of praise of his work when tears flowed heavily from his eyes. He tried to speak, but his lips only quivered in the strongest Parkinson’s tremors I’d ever seen on him. He lifted his picture and in a staggering gait, rushed from the room. I started to follow but Debbie held my arm. All the reassurances and praise I’d given with the other “bad” paintings were left unsaid.

“He’ll be alright,” she said again. I thought she would follow and comfort him but instead she went upstairs to the bedroom there.

I was aghast at that scene. Debbie’s words disturbed me, words that to this day she denies she ever said. But I was there as she uttered those derogatory remarks. Dr. Kampmeier’s admonitions rang in my ears as I thought of the damage her words might have on my friend. I regret that I did not have a camera to photograph that picture.

I couldn’t sleep for several nights. I called often but Barclay never lifted the phone. When Debbie answered, she said that he’d “get over it and call me soon”. Christmas passed without my usual visit to the artist and our holiday drink. He always gave me a painting. My usual gift to him was a bottle of whiskey, a bottle of good quality wine, or some article of hunting equipment or apparel. One of my Christmas gifts to him was a painting, one by the well-recognized artist of the past, Elliot Dangerfield, whose own art first came under scrutiny after he published the initial biographies of Hudson River School artists George Inness and Ralph Blakelock. These books initiated widespread recognition of these two men as well as his own paintings, as I hope my upcoming biography will gain for Barclay.

I went to his home several times and knocked, but he was never available. Then in the first week in January, I received a call from him with the brief message: “I have a picture for you.”

I hastened there and Debbie ushered me to his studio. He looked at me in a quizzical manner such as he’d never before displayed. He pointed to his easel. There I saw the shock of my life. On the same canvass on which he’d painted that perfectly awful picture a month before was a real Barclay Sheaks work, in the style of his many masterpieces of the past (Figure 37). I could have cried, tears of joy at that moment. I was speechless but he knew I was pleased. From all his Parkinson’s tainted paintings in my attic facing the wall, I’d expected this day I would carry home another to add to that group. But that one was destined to hang on my favorite wall with my best paintings. I was as happy to pay his price for the picture as he was to receive my check. Barclay and I were never “huggers”, but that day I gave him a big one.