Trunk Motel

Who Has Your Back

Who is willing to weather the storms in your life with you? Who has your back? This is slightly different than what I mentioned in the chapter, “Clinging to a Lifeline.” I am referring here to a person or the people that actually seek you out and are present when the sprinkles in life turn into a torrential downpour. There is no hesitation, no need to call or ask, because they simply show up on their own and offer assistance for as long as is necessary.

In early June of 2006, I had flown into Seattle, Washington by myself with some bike gear. After travelling by bus to Burlington, I stayed at the prearranged church for two days. I had shipped my recumbent in a bike box the week before. I put my bike together that first day, and since it was sunny, decided to ride the dozen miles to the coast and Padilla Bay so I could say I actually started my cross-country ride at the Pacific Ocean. While dipping my back wheel into the water, I certainly was excited as I anticipated the eastward push. But I also felt a bit odd.

After all the fundraising and preparation of overnight accommodations, the ride was actually a reality. An almost sad feeling came over me while I sat looking at the Pacific Ocean. I realized that this trip would not only be a milestone in cycling for me, but I would probably never repeat it again. At 48 years of age and crossing the continental 48, I might never again attempt such a trip. The likelihood of trying to cross two great mountain ranges again, like the Northern Cascades and the Rockies, in ten days of riding seemed remote. It felt much like a planned for and long awaited occasion, like Christmas, when there is a letdown afterward. The reality never quite matches the hype. I had planned and trained for this ride for a year, and in six weeks it would be over.

On my first day of the trip while entering the Northern Cascades of Washington State, my wife and a friend named Mary met me on the western slopes as I began to climb. We camped at Lake Diablo at the base of two serious climbs, Rainy and Washington Pass, that I would ride over the following day. While not the subject of this chapter, the sense of accomplishment over cresting those two passes on the second day of the trip was overwhelming. The dozens of small waterfalls on the side of the road from the snow melt and the snow drifts, still present at the top of each pass, were amazing. The amount of strain put on my legs by that ride was equally impressive.

Rita treated me to a massage by a therapist at our third overnight stop in Republic, Washington after having gone over two more mountain passes after leaving Twisp earlier that day. A typical massage is a delightful experience, but my legs were very sore and prone to spontaneous cramping, making the massage of my legs closer to agony. But I tolerated the intense pain since I knew it was the best thing for my leg muscles. I knew from previous experience that my leg muscles would get used to the long miles each day, so the massage was a welcome treat, even if a painful one at the time.

Republic sits isolated between two mountain passes, Wauconda Pass, which I had just descended, and Sherman Pass, which was my task the next day. We stayed in a church hall where we were to use our sleeping bags and pads as our bedding for the night on the hall floor. I visited briefly with the elderly pastor of the church. Father George stated that he keeps on with his ministry because no one else wants to come. The town can get snowed in for a week at a time in the winter. I looked online for the weather forecast at the pastor’s residence. Sherman Pass, the highest elevation for the entire trip at 5800+ ft. seemed doable after the confidence I had gained the past two days. The forecast stated a chance of rain briefly in the morning followed by clearing skies.

I crawled out of my sleeping bag just before dawn and quietly told my wife I would see her up the road in a couple hours. The skies were cloudy, and even though it was cool, it did not take me long to peel off the outer layer of bike clothes as I started to sweat a lot with the serious climb. In my short-sleeved bike shirt and shorts, I started to hear the telltale sound of thunder a half hour into the climb. The thunder grew louder and it started to sprinkle. I put on my rain gear as the rain began to fall in earnest. When I heard and saw the brightening of the sky due to lightning, I looked for a place to ditch my bike and get under cover.

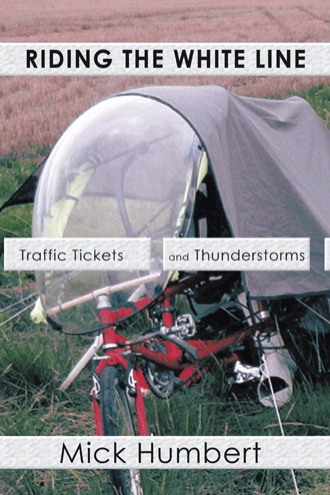

There were no buildings, just dense forest and underbrush. As good fortune would have it, I saw a wooden fence and a small makeshift gate where a vehicle would pass through on the right side of the road. I thought at least the trek through the thick underbrush into the forest would be somewhat easier if I followed the tracks and hopped over the gate. I always carried a rain fly from a banana-shaped tent with me to cover the bike, and myself if necessary, in heavy rain. I ditched the bike with the rain fly over it, and headed into the woods, despite the “no trespassing” sign, because I did not want to be too close to the metal bike with lightning in the area.

Trunk Motel

Who Has Your Back

Who is willing to weather the storms in your life with you? Who has your back? This is slightly different than what I mentioned in the chapter, “Clinging to a Lifeline.” I am referring here to a person or the people that actually seek you out and are present when the sprinkles in life turn into a torrential downpour. There is no hesitation, no need to call or ask, because they simply show up on their own and offer assistance for as long as is necessary.

In early June of 2006, I had flown into Seattle, Washington by myself with some bike gear. After travelling by bus to Burlington, I stayed at the prearranged church for two days. I had shipped my recumbent in a bike box the week before. I put my bike together that first day, and since it was sunny, decided to ride the dozen miles to the coast and Padilla Bay so I could say I actually started my cross-country ride at the Pacific Ocean. While dipping my back wheel into the water, I certainly was excited as I anticipated the eastward push. But I also felt a bit odd.

After all the fundraising and preparation of overnight accommodations, the ride was actually a reality. An almost sad feeling came over me while I sat looking at the Pacific Ocean. I realized that this trip would not only be a milestone in cycling for me, but I would probably never repeat it again. At 48 years of age and crossing the continental 48, I might never again attempt such a trip. The likelihood of trying to cross two great mountain ranges again, like the Northern Cascades and the Rockies, in ten days of riding seemed remote. It felt much like a planned for and long awaited occasion, like Christmas, when there is a letdown afterward. The reality never quite matches the hype. I had planned and trained for this ride for a year, and in six weeks it would be over.

On my first day of the trip while entering the Northern Cascades of Washington State, my wife and a friend named Mary met me on the western slopes as I began to climb. We camped at Lake Diablo at the base of two serious climbs, Rainy and Washington Pass, that I would ride over the following day. While not the subject of this chapter, the sense of accomplishment over cresting those two passes on the second day of the trip was overwhelming. The dozens of small waterfalls on the side of the road from the snow melt and the snow drifts, still present at the top of each pass, were amazing. The amount of strain put on my legs by that ride was equally impressive.

Rita treated me to a massage by a therapist at our third overnight stop in Republic, Washington after having gone over two more mountain passes after leaving Twisp earlier that day. A typical massage is a delightful experience, but my legs were very sore and prone to spontaneous cramping, making the massage o